“TODAY WE SEE the birth of a new species,” declared Julio Friedmann, gazing across the bleak landscape. Along with several hundred grandees, the renowned energy technologist had travelled to a remote corner of Texas’s oil patch called Notrees at the end of April at the invitation of 1PointFive, a division of Occidental Petroleum, an American oil firm, and of Carbon Engineering, a Canadian technology startup backed by Bill Gates. The species in question is in some ways akin to a tree—but not the biological sort, nowhere to be seen on the barren terrain. Rather, it is an arboreal artifice: the first commercial-scale “direct air capture” (DAC) plant in the world.

Like a tree, DAC sucks carbon dioxide from the air, concentrates it and makes it available for some use. In the natural case, that use is creating organic molecules through photosynthesis. For DAC, it can be things for which humans already use CO2, like adding fizz to drinks, encouraging faster plant growth in greenhouses or, in Occidental’s case, injecting it into underground oil reservoirs to squeeze more drops of crude from the nooks and crannies.

Yet some of the 500,000 tonnes of CO2 that the Notrees plant will capture each year once fully operational in 2025 will be pumped beneath the Texas plains in the service of a grander goal: fighting climate change. For unlike the carbon stored in biological plants, which can be released when they are cut down or burned, CO2 artificially sequestered may well stay sequestered indefinitely. Companies that want to net out some of their own carbon emissions but do not trust biology-based offsets will pay the project’s managers per stashed tonne. That makes the Notrees launch the green shoot of a something else, too: a real industry.

Carbon Engineering and its rivals, such as ClimeWorks, a Swiss firm, Global Thermostat, a Californian one, and myriad startups worldwide, are attracting private capital. Occidental plans to build 100 large-scale DAC facilities by 2035. Others are trying to mop up carbon dioxide produced by power plants and industrial processes before it even enters the atmosphere, an approach known as carbon capture and storage (CCS). In April ExxonMobil unveiled ambitious plans for its newish low-carbon division, whose long-term goal is to offer such decarbonisation as a service for industrial customers in sectors, like steel and cement, whose emissions are otherwise hard to abate. The oil giant thinks this sector could be raking in annual revenues of $6trn globally by 2050.

The boom in carbon removal, be it from the atmosphere or from industrial point sources, cannot come fast enough. The UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assumes that if the world is to have a chance of limiting global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, in line with the Paris climate agreement, renewables, electric vehicles and other decarbonisation technologies are not enough. CCS and sources of “negative emissions” such as DAC will need to play a part.

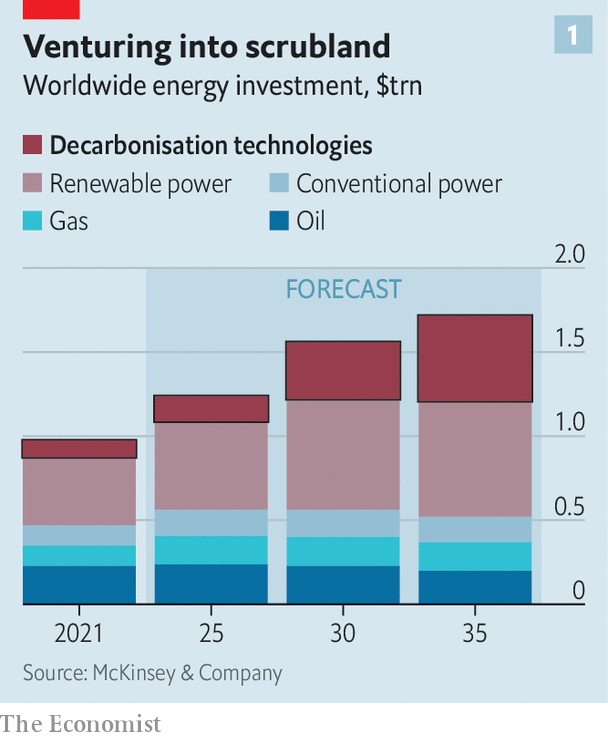

America’s Department of Energy calculates that the country’s climate targets require capturing and storing between 400m and 1.8bn tonnes of CO2 annually by 2050, up from 20m tonnes today. Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy, reckons that globally various forms of carbon removal account for a fifth of the emissions reductions required to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050. If Wood Mackenzie is right, and given that humanity belches more than 40bn tonnes a year, this would be equivalent to sucking up more than 8bn tonnes of CO2 annually. And that requires an awful lot of industrial-scale carbon-removal ventures (see chart 1).

For years such projects were regarded as technically plausible, perhaps, but uneconomical. An influential estimate by the American Physical Society in 2011 put the cost of DAC at $600 per tonne of CO2 captured. By comparison, permits to emit one tonne currently trade at around $100 in the EU’s emissions-trading system. CCS has been a perennial disappointment. Simon Flowers of Wood Mackenzie notes that the power sector has spent some $10bn over the years trying to get the technology to work without much to show for it.

Backers of the new crop of carbon-removal projects think this time is different. One reason for their optimism is better and, crucially, cheaper technology (see chart 2). The cost of sequestering a tonne of CO2 beneath Notrees has not been disclosed but a paper from 2018 published in the journal Joule put the price tag for Carbon Engineering’s DAC system at between $94 and $232 per tonne when operating at scale. That is much less than $600 and not a world away from the EU’s carbon price.

CcS, which should be considerably cheaper than DAC, is also showing a bit more promise. Svante, a Canadian startup, uses inexpensive materials to capture CO2 from dirty industrial flue gas for around $50 a tonne (though that price tag excludes transport and storage). Other companies are converting the captured carbon into products which they then hope to sell at a profit. CarbonFree, which works with US Steel and BP, a British oil-and-gas company, takes CO2 from industrial processes and turns it into speciality chemicals. LanzaTech, which has a commercial-scale partnership with ArcelorMittal, a European steel giant, and several Chinese industrial firms, builds bioreactors that convert industrial carbon emissions into useful materials. Some make their way into portable carbon stores, such as Lululemon yoga pants.

All told, carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS in the field’s acronym-rich jargon) is set to attract $150bn in investments globally this decade, predicts Wood Mackenzie. Assessing current and proposed projects, the consultancy reckons that global CCUS capacity—which on its definition includes cCS, the sundry ways to put the captured carbon to use, as well as DAC—will rise more than seven-fold by 2030.

The second—possibly bigger—factor behind the recent flurry of carbon-removal activity is government action. One obvious way to promote the industry would be to make carbon polluters pay a high-enough fee for every tonne of carbon they emit that it would be in their interest to pay carbon removers to mop it all up, either at the source or from the atmosphere. A reasonable carbon price like the EU’s current one may, just about, make CCS viable. For DAC to be a profitable enterprise, though, the tax would probably need to be a fair bit higher, which could smother economies still dependent on hydrocarbons. That, plus the dim prospects for a global carbon tax, means that state support is needed to bridge the gap between the current price of carbon and the cost of extracting it.

The emerging view among technologists, investors and buyers is that carbon capture will develop in the way that waste management did decades ago—as an initially costly but necessary endeavour that needs public support to get off the ground but can in time become profitable. That view is increasingly also held by policymakers.

Some of the hundreds of billions of dollars in America’s recently approved climate handouts are aimed at bootstrapping the carbon-removal industry into existence. An enhanced tax credit included in one of the laws, the Inflation Reduction Act, provides up to $85 per tonne of CO2 permanently stored (as well as $60 per tonne of CO2 used for enhanced oil recovery, which also sequesters CO2 albeit in order to produce more hydrocarbons). Clio Crespy of Guggenheim Securities, an investment firm, calculates that this credit increases the volume of emissions in America that are “in the money” for carbon removal more than ten-fold. The EU’s response to America’s climate bonanza is likely to promote carbon removal, too. Earlier this year the EU and Norway announced a “green alliance” to boost regional carbon-capture plans.

With the price of scrubbing a tonne of CO2 no longer completely otherworldly, buyers are beginning to line up. Big tech, with deep pockets and a progressive image to burnish, is particularly keen. On May 15th Microsoft unveiled plans to purchase (for an undisclosed sum) more than 2.7m tonnes of carbon captured over a decade from biomass-burning power plants in Denmark run by Orsted, a big Danish clean-energy firm, and transported for underground sequestration in the North Sea by a consortium involving Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies, three European oil giants. Three days later Frontier, a buyers’ club with a $1bn pot for carbon-removal investments bankrolled mainly by Alphabet, Meta, Stripe and Shopify, announced a $53m deal with Charm Industrial. The firm will remove 112,000 tonnes of CO2 between 2024 and 2030 by converting agricultural waste, which would otherwise emit carbon as it decomposes, into an oil that can be stored underground.

Carbon middlemen are emerging to connect projects and buyers. NextGen, a joint venture between Mitsubishi Corporation, a Japanese conglomerate, and South Pole, a Swiss developer of carbon-removal and -management projects, intends to acquire over 1m tonnes in certified carbon-removal credits by 2025, and has lined up big buyers. It has just announced the purchase of nearly 200,000 tonnes’ worth of carbon credits from 1PointFive and two other ventures. The end buyers include SwissRe and UBS, two Swiss financial giants, Mitsui OSK Lines, a Japanese shipping company, and Boston Consulting Group.

Maybe the biggest sign that the carbon-removal business has legs is its embrace by the oil industry. Occidental is keen on DAC. ExxonMobil says it will spend $17bn from 2022 to 2027 on “lower-emissions investments”, with a big slug going to ccs. Chevron, ExxonMobil’s main American rival, is hosting Svante at one of its Californian oilfields. As the Microsoft deal shows, their European counterparts want to convert parts of the North Sea floor into a giant carbon sink. Equinor and Wintershall, a German oil-and-gas firm, have already secured licences to stash carbon captured from German industry in North Sea sites. Hugo Dijkgraaf, Wintershall’s technology chief, thinks his firm can abate up to 30m tonnes of CO2 per year by 2040. The idea, he says, is to turn “from an oil-and-gas company into a gas-and-carbon-management company”.

Saudi Arabia, home to Saudi Aramco, the world’s oil colossus, has set itself a goal of increasing its CCS capacity five-fold in the next 12 years. Its mega-storage facility at Jubail Industrial City is expected to be operational by 2027. ADNOC, the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company, wants to ramp up its capacity six-fold by 2030, to 5m tonnes per year.

The oilmen’s critics allege that their enthusiasm for carbon removal is mainly about improving their reputations in the eyes of increasingly climate-conscious consumers, while pumping more crude for longer. There is surely some truth to this. But given the urgent need to both capture carbon at source and achieve voluminous negative emissions, the willing involvement of giant oil firms, with their vast capital budgets and useful expertise in engineering and geology, is to be welcomed.