HAVING JUST surpassed China as the world’s most populous country, India contains more than 1.4bn people. Its migrants are both more numerous and more successful than their Chinese counterparts. The Indian diaspora has been the largest in the world since 2010.

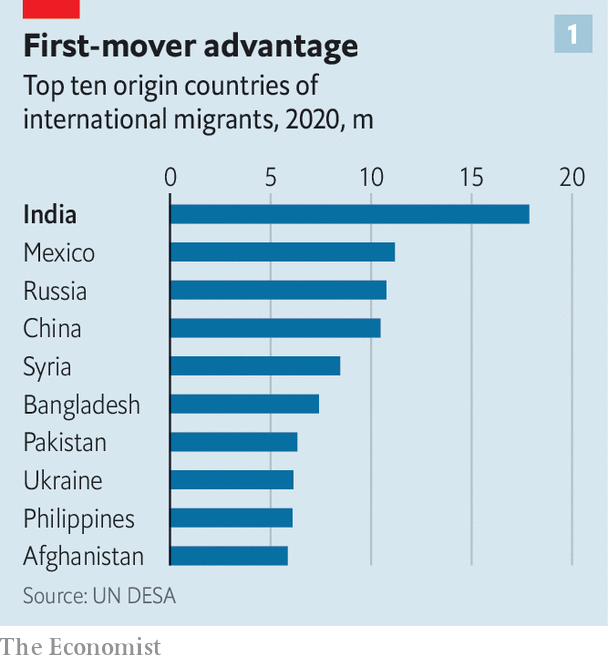

Of the 281m migrants spread around the globe today—generally defined as people who live outside the country where they were born—almost 18m are Indians, according to the latest UN estimates from 2020. Mexican migrants, the second-biggest group, number just 11.2m. Chinese abroad number 10.5m.

Understanding how and why Indians have secured success abroad, while Chinese have sown suspicion, illuminates geopolitical faultlines. Comparing the two groups also reveals the extent of Indian achievement. The diaspora’s triumphs advance India and benefit its prime minister, Narendra Modi. Joe Biden will host talks with him on June 22nd as part of Mr Modi’s forthcoming state visit to America.

Migrants have stronger ties to their motherlands than do their descendants born abroad, and so build vital links between their adopted homes and their birthplaces. In 2022 India’s inward remittances hit a record of almost $108bn, around 3% of GDP, more than in any other country. And overseas Indians with contacts, language skills and know-how boost cross-border trade and investment.

Huge numbers of second-, third- and fourth-generation Chinese live abroad, notably in South-East Asia, America and Canada. But in many rich countries, including America and Britain, the Indian-born population exceeds the Chinese-born (see chart 1).

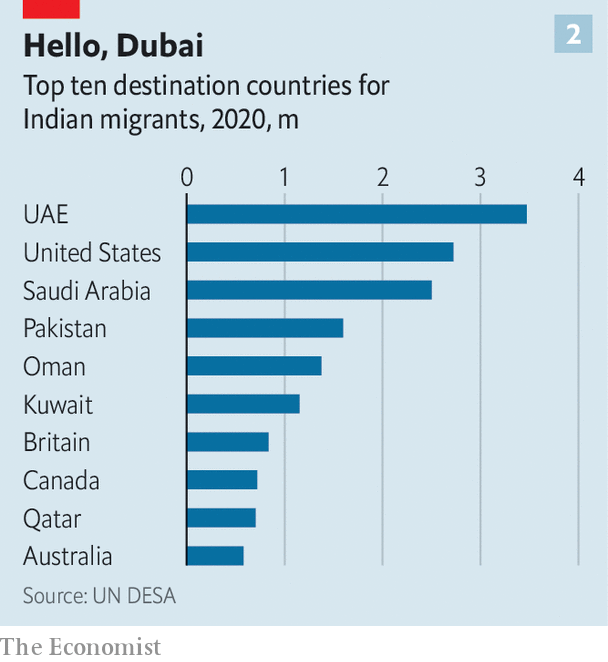

India’s people are found across the world (see chart 2), with 2.7m of them living in America, more than 835,000 in Britain, 720,000 in Canada, and 579,000 in Australia. Young Indians flock to the Middle East, where low-skilled construction and hospitality jobs are better-paid. There are 3.5m Indian migrants in the United Arab Emirates and 2.5m in Saudi Arabia (where the UN counts Indian citizens as a proxy for the Indian-born population). Many more dwell in Africa, other parts of Asia and the Caribbean, part of a migration route that dates back to the colonial era.

India has the essential ingredients to be a leading exporter of talent: a mass of young people and first-class higher education. Indians’ mastery of English, a legacy of British colonial rule, probably helps, too. Only 22% of Indian immigrants in America above the age of five say they have no more than a limited command of English, compared with 57% of Chinese immigrants, according to the Migration Policy Institute (mpi), an American think-tank.

As India’s population grows over the coming decades, its people will continue to move overseas to find jobs and escape its heat. Immigration rules in the rich world filter for graduates who can work in professions with demand for more employees, such as medicine and information technology. In 2022 of America’s H-1B visas, for skilled workers in “speciality occupations”, such as computer scientists, 73% were won by people born in India.

Many of India’s best and brightest seem to prepare themselves to migrate. Consider the findings of a paper soon to be published in the Journal of Development Economics by Prithwiraj Choudhury of Harvard Business School, Ina Ganguli of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Patrick Gaule of the University of Bristol. It considered students that took the highly competitive entrance exams for the Indian Institutes of Technology, the country’s elite engineering schools, in 2010. Eight years later, the researchers found that 36% of the 1,000 top performers had migrated abroad, rising to 62% among the 100 best. Most went to America.

Another study looked at the top 20% of researchers in artificial intelligence (defined as those who had papers accepted for a competitive conference in 2019). It found that 8% did their undergraduate degree in India. But the share of top researchers that now work in India is so small that the researchers did not even record it.

In America almost 80% of the Indian-born population over school age have at least an undergraduate degree, according to number-crunching by Jeanne Batalova at the mpi. Just 50% of the Chinese-born population and 30% of the total population can say the same. It is a similar story in Australia, where almost two-thirds of the Indian-born population over school age, half the Chinese-born and just one-third of the total population has a bachelor’s or higher degree. Other rich countries do not collect comparable data.

Softly, softly

Joseph Nye, a Harvard professor who coined the phrase “soft power“, notes that it is not automatically created by the mere presence of a diaspora. “But if you have people in the diaspora who are successful and create a positive image of the country from which they came, that helps their native country.” And, as he notes “India has a lot of very poor people but they are not the people coming to the United States.”

Indeed Indian migrants are relatively wealthy even in the countries they have moved to. They are the highest-earning migrant group in America, with a median household income of almost $150,000 per year. That is double the national average and well ahead of Chinese migrants, with a median household income of over $95,000. In Australia the median household income among Indian migrants is close to $85,000 per year, compared with an average of roughly $60,000 across all households and $56,500 among the Chinese-born.

The might of the Indian diaspora is increasingly on display at the pinnacle of business and the apex of government. Devesh Kapur and Aditi Mahesh at Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC, totted up the number of people with Indian roots in top jobs, including those born in India and those whose forebears were. They identified 25 chief executives at S&P 500 companies of Indian descent, up from 11 a decade ago. Given the large number of Indian-origin executives in other senior positions at these companies, that figure is almost sure to rise further.

It is only recently that Indians abroad have begun to win such prestigious posts. Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, a computer-maker, recalls how difficult it was for Indian entrepreneurs to raise money in 1980s America. “You were people with a funny accent and a hard to pronounce name and you had to pass a higher bar,” he says. Now Adobe, Alphabet, Google’s corporate parent, IBM and Microsoft are all led by people of Indian descent. The deans at three of the five leading business schools, including Harvard Business School, are of Indian descent, too.

In the world of policy and politics, the Indian diaspora is also thriving. The Johns Hopkins researchers have counted 19 people of Indian heritage in Britain’s House of Commons, including the prime minister, Rishi Sunak. They identified six in the Australian parliament and five in America’s Congress. Vice-President Kamala Harris was brought up by a Tamil Indian mother. And Ajay Banga, born in Pune in India, was selected to lead the World Bank last month after running MasterCard for more than a decade.

The Chinese diaspora is the only other group with comparable influence around the world. The richest man in Malaysia, for example, is Robert Kuok, an ethnic-Chinese businessman whose vast empire includes the Shangri-La hotels. But in Europe and North America, people of Chinese descent do not hold as many influential positions as their Indian counterparts.

Binding Delhi and DC

As America drifts towards a new cold war with China, Westerners increasingly see the country as an enemy. The covid-19 pandemic, which began in the Chinese city of Wuhan, probably made matters worse. In a recent survey of Americans’ attitudes by Gallup, a pollster, 84% of respondents said they viewed China mostly or very unfavourably. On India, only 27% of people surveyed held the same negative views.

This mistrust of China percolates through policy. Huawei, a Chinese telecoms-equipment manufacturer suspected in the past of embargo-busting and of being a conduit for Chinese government spying, has been banned in America. Some European countries are following suit. Stringent reviews of foreign investments in American companies on national-security grounds openly target Chinese money in Silicon Valley. Individuals found to be doing China’s bidding, including one ex-Harvard professor, have been punished. Indian firms do not face such scrutiny.

The Indian government, by contrast, has been—at least until Mr Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) took over—filled with people whose view of the world had been at least partly shaped by an education in the West. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, studied at Cambridge. Mr Modi’s predecessor, Manmohan Singh, studied at both Oxford and Cambridge.

India’s claims to be a democratic country steeped in liberal values help its diaspora integrate more readily in the West. The diaspora then binds India to the West in turn. The most stunning example of this emerged in 2008, when America signed an agreement that, in effect, recognised India as a nuclear power, despite its never having signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (along with Pakistan and Israel). Lobbying and fundraising by Indian-Americans helped push the deal through America’s Congress.

The Indian diaspora gets involved in politics back in India, too. Ahead of the 2014 general election, when Mr Modi first swept to power, one estimate suggests more than 8,000 overseas Indians from Britain and America flew to India to join his campaign. Many more used text messages and social media to turn out BJP votes from afar. They contributed unknown sums of money to the campaign.

Under Mr Modi, India’s ties to the West have been tested. In a bid to reassert its status as a non-aligned power, India has refused to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and stocked up on cheap Russian gas and fertiliser. Government officials spew nationalist rhetoric that pleases right-wing Hindu hotheads. And liberal freedoms are under attack. In March Rahul Gandhi, leader of the opposition Congress party, was disqualified from parliament on a spurious defamation charge after an Indian court convicted him of criminal defamation. Meanwhile journalists are harassed and their offices raided by the authorities.

Overseas Indians help ensure that neither India nor the West gives up on the other. Mr Modi knows he cannot afford to lose their support and that forcing hyphenated Indians to pick sides is out of the question. At a time when China and its friends want to face down a world order set by its rivals, it is vital for the West to keep India on side. Despite its backsliding, India remains invaluable—much like its migrants.