Tesla’s surprising new route to EV domination -Become more like the industry you disrupte

전기 자동차 지배를 향한 테슬라의 놀라운 새로운 경로 당신이 파괴한 업계처럼 되기

IN 2011 TESLA stated an aim of becoming “the most compelling car company of the 21st century, while accelerating the world’s transition to electric vehicles”. At the time this was easy to dismiss as crackers. In the eight years since its founding in 2003 the firm had manufactured a piddling 1,650 EVs. Its first big-selling car, the Model S, had yet to hit the road.

I

N 2011 TESLA는 "세계의 전기 자동차로의 전환을 가속화하면서 21세기의 가장 매력적인 자동차 회사"가 되는 목표를 밝혔습니다. 그 당시 이것은 크래커로 기각하기 쉬웠습니다. 2003년 설립 이후 8년 동안 이 회사는 보잘것없는 1,650대의 EV를 제조했습니다. 첫 번째로 많이 팔린 자동차인 모델 S는 아직 출시되지 않았습니다.

Today it is almost as mad to argue that Elon Musk, the carmaker’s boss since 2008, has not achieved that goal. His company, a rare insurgent in an industry with formidable barriers to entry, has grown at neck-snapping speed. In the first quarter of 2023 Tesla’s Model Y mini-SUV was the world’s bestselling car. In the second quarter it delivered a total of 466,000 cars, beating analysts’ forecasts (see chart 1). Mr Musk’s promise of 2m sales this year, up from 1.3m in 2022, no longer seems fanciful. On July 15th the first Cybertruck, an angular, retro-futuristic pickup, rolled off the production line. Tesla has just unveiled an expansion plan for its German factory, where it wants to double capacity to 1m vehicles per year.

Besides almost single-handedly reimagining the car, Mr Musk has done the same to the car industry. His focus on streamlined manufacturing of only a handful of models has kept costs at bay. Last year Tesla boasted operating margins of 17%; among non-niche carmakers only Porsche, which churns out fewer than 1m cars annually, matched its performance.

Mr Musk’s ambition to dominate the auto business—by making 20m cars a year by 2030, double the current output of today’s top manufacturer, Toyota, and by creating the go-to self-driving system—certainly compels investors, who value Tesla at around $900bn. That is down from over $1trn in early 2022 but still more than the next nine most valuable carmakers put together. Incumbents are scrambling to electrify their product ranges and to copy Mr Musk’s vertically integrated approach to production, while fending off a wave of EV newcomers, many of them Chinese, all trying to be the next Tesla.

The question now is whether Tesla can keep growing as fast and as profitably as it has for much longer. In its latest quarterly earnings on July 19th, it reported margins of 9.6%, even lower than the 11.4% it eked out in the three previous months, as it slashed prices in order to compete with cheaper rivals (see chart 2). Its advantages as a disruptive tech firm with a Silicon Valley mindset are in danger of being eroded. To make even 5m-6m cars a year this decade, a more realistic target than Mr Musk’s goal of 20m, would require “embracing the techniques of legacy auto”, observes Dan Levy of Barclays, a bank. In order to remain a disruptive force, Tesla may, paradoxically, need to become a bit more like the stodgy car business it has shaken up.

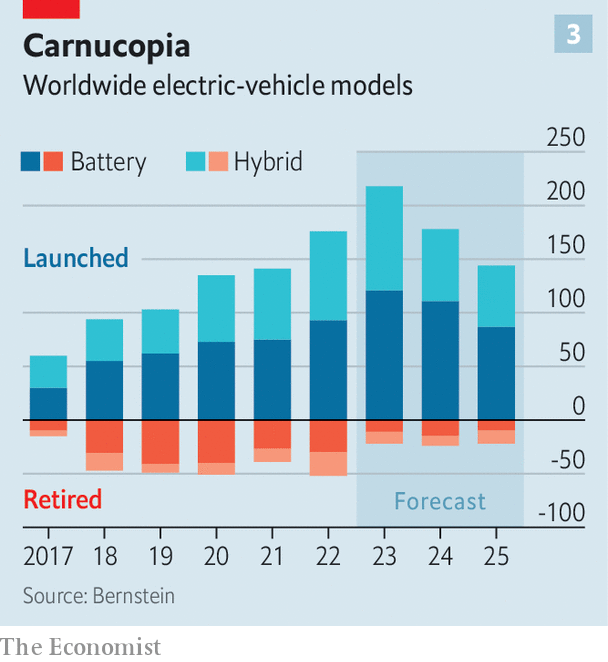

Tesla maintains a lead over its more established rivals in batteries, software and manufacturing productivity, notes Philippe Houchois of Jefferies, an investment bank. But competitors are catching up. In some areas, like marketing and product planning, they have overtaken it, notes Mr Houchois. When it launched the Model S—large and pricey with big batteries and a long range—it had the EV market largely to itself. Nowadays motorists can choose between 500 or so EV models from dozens of marques. Bernstein, a broker, estimates that around 220 new models may be launched this year and another 180 in 2024 (chart 3). For Tesla to grow fast in the face of all this competition will be difficult.

Unlike incumbent carmakers’ “something for everybody” approach, Tesla manufactures just five models (if you count the Cybertruck) and relies heavily on two of them. The Model 3, a small saloon, and the Model Y account for 95% of the vehicles Tesla shifts. By comparison, Toyota’s two bestsellers, Corolla and RAV4, make up just 18% of the vehicles sold by the Japanese firm. For Tesla to hit its target of selling a combined 3m-4m Model 3s and Model Ys, each model would need to control 50% of the cars in its class ($40,000-60,000 mass-market cars and $45,000-65,000 SUVs, respectively). According to Bernstein, no carmaker has ever had more than 10% in those two segments

Off the marque

And both models are ageing. The Model Y is three years old and the Model 3 has just turned six, which makes them less desirable in a business where novelty has historically counted for a lot. Carmaking’s rule of thumb to keep sales chugging along is to refresh models every 2-4 years and redesign them completely every 4-7 years. Tesla’s planned “refresh” of the Model 3’s styling and its tech innards this year looks late by industry standards.

The company will need to go well beyond its current strategy, of offering software updates that improve some of its cars’ features, or that add new ones. This may have done the trick for its original customer base of early-adopter techies but is unlikely to cut it with the average motorist. One solution is to offer more options for its existing range. Barclays estimates that the Model 3 comes in 180 configurations, a fraction of the 195,000 trims for a comparable (petrol-powered) BMW 3 Series saloon. But this would introduce the sort of complexity Mr Musk has hitherto shunned.

Another route to higher sales is to launch new models, like the Cybertruck or a low-cost mass-market vehicle—unofficially called the “Model 2” and with prices starting at $25,000—which Mr Musk has promised to start selling in the next couple of years. New models, though, come with new challenges. The relevant pickup market, with global sales of 1.3m, according to Bernstein, is relatively modest—and the Cybertruck’s bold styling may limit its appeal. And though low-cost Teslas could expand the company’s market beyond America, China and Europe, they would almost certainly generate lower margins, further depressing the company’s overall profitability. Moreover, granting regional ventures greater autonomy to manage regional differences in taste, as established carmakers have historically done, again adds complexity and costs.

Mr Musk may no longer be able to avoid other expensive industry practices. One is marketing. In contrast to all other big carmakers, which spend princely sums on ads, Tesla has depended on word-of-mouth and Mr Musk’s own larger-than-life persona to promote its products. Barclays reckons that eschewing ads and, by selling directly to buyers, bypassing dealers, currently saves the company $2,500-4,000 for every car it sells. As it seeks new customers, and as Mr Musk risks affecting Tesla sales with his polarising stewardship of Twitter, his $44bn side-project, the company is likely to forgo some of those savings. Mr Musk has conceded as much, saying that, for the first time, his company might “try a little advertising”.

Another carmaking staple to which Tesla has belatedly come around is price cuts. Mr Musk had pledged never to offer discounts or allow inventory to build up. His company has lately done both. Production exceeded sales in the past five quarters. After growing at an average annual rate of 60% for years, quarterly sales volumes expanded by an average of 30-40% between the second quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. To shift more vehicles Mr Musk began slashing prices late last year, by up to 25% on some models. Sales duly ballooned, by more than 80% in the second quarter, compared with a year ago. The flipside was those duly contracting margins. Investors have tolerated Mr Musk’s price cuts more than in the case of his rivals: on July 17th Ford’s share price fell by 6% after it announced hefty discounts on its F-150 Lightning EV pickup. They may not stay so forgiving for ever.

As its various costs rise, Tesla will try to keep cutting them elsewhere, notably in manufacturing. In March it unveiled what it called the “unboxed process”, designed to make cars “significantly simpler and more affordable” by streamlining or even eliminating stages of production. It is unclear what exactly Mr Musk has in mind. Despite his record of engineering ingenuity, at least one previous attempt to up-end car manufacturing, by replacing people with robots for the Model 3, led to what Mr Musk himself candidly described as “production hell” and near-bankruptcy in 2018.

Mr Musk’s last fresh challenge—and another one he shares with incumbent Western carmakers—is what to do about China. Tesla, which makes more than half its cars at its giant factory in Shanghai, no longer seems to hold its privileged position in the country. It was allowed to set up without the Chinese joint-venture partner required of other foreign carmakers, at a time when China needed Mr Musk to supply EVs for Chinese motorists and, importantly, to encourage China’s own budding EV industry to raise its game.

That has worked too well. Tesla is thought to have sold 155,000 cars in China in the second quarter, 13% more than in the previous three months. But China Merchants Bank International Securities, an investment firm, reckons its market share may have slipped below 14%, from 16% in the preceding quarter, as buyers switched to fast-improving home-grown brands. In a sign that Tesla now needs China more than China needs Tesla, the company was obliged to sign a pledge on July 6th with other car firms to stop its price war and compete fairly in line with “core socialist values”. Tu Le of Sino Auto Insights, a consultancy, says rumours are rife that the Chinese authorities are pushing back against Tesla’s efforts to increase manufacturing capacity in China. And that is before getting into the increasingly fraught geopolitics of Sino-American commerce.

If Tesla is to sell 6m cars a year at an operating margin of 14% by 2030, which Mr Levy of Barclays thinks possible, it probably needs to avoid at least some of these pitfalls. It would be foolish to dismiss that eventuality, given Tesla’s knack for confounding sceptics. It could, for example, offset part of the decline in sales growth with new revenue streams, such as recent deals to open its charging network to Ford and General Motors customers. As brands become defined by the digitally mediated experience of driving rather than the body shell or handling, its superior software—including, one day, self-driving systems—may allow it to keep offering fewer models than its rivals. Mr Le thinks Tesla will mitigate the China risk by manufacturing more of its cars in Germany and other countries, including low-cost ones. Tesla has been by far the most compelling car company of the early 21st century. If it is to hold on to that title, it must work for it.

브랜드 끄기

그리고 두 모델 모두 노후화되고 있습니다. Model Y는 출시된 지 3년이 되었고 Model 3는 이제 막 6년이 되었기 때문에 역사적으로 참신함이 중요한 비즈니스에서 덜 바람직합니다. Carmaking의 경험 법칙에 따르면 2~4년마다 모델을 교체하고 4~7년마다 완전히 재설계하는 것이 판매를 계속 유지하는 것입니다. 올해 Tesla가 계획한 Model 3의 스타일과 기술 내장에 대한 "새로 고침"은 업계 표준에 따라 늦은 것으로 보입니다.회사는 자동차의 일부 기능을 개선하거나 새로운 기능을 추가하는 소프트웨어 업데이트를 제공하는 현재 전략을 훨씬 뛰어 넘어야 할 것입니다. 이것은 얼리 어답터 기술자의 원래 고객 기반에 대한 트릭을 수행했을 수 있지만 일반 운전자와 함께 자르지 않을 것입니다. 한 가지 해결책은 기존 범위에 대해 더 많은 옵션을 제공하는 것입니다. Barclays는 Model 3가 180개의 구성으로 제공될 것으로 추정하며, 이는 비슷한(가솔린) BMW 3 시리즈 세단의 195,000개 트림 중 일부입니다. 그러나 이것은 머스크 씨가 지금까지 피했던 종류의 복잡성을 도입할 것입니다.

더 높은 판매를 위한 또 다른 경로는 Cybertruck 또는 저렴한 대중 시장 차량(비공식적으로 "모델 2"라고 하며 가격이 $25,000부터 시작하는)과 같은 새로운 모델을 출시하는 것입니다. 년. 그러나 새 모델에는 새로운 문제가 따릅니다. 번스타인에 따르면 전 세계적으로 130만대가 판매되는 관련 픽업 시장은 상대적으로 완만하며 사이버트럭의 대담한 스타일은 그 매력을 제한할 수 있습니다. 그리고 저비용 Tesla가 미국, 중국 및 유럽을 넘어 회사의 시장을 확장할 수는 있지만 거의 확실하게 더 낮은 마진을 생성하여 회사의 전반적인 수익성을 더욱 떨어뜨릴 것입니다. 게다가 기존 자동차 제조업체가 역사적으로 그랬던 것처럼 지역적 취향 차이를 관리할 수 있는 더 큰 자율성을 지역 벤처에 부여하면 다시 복잡성과 비용이 추가됩니다.머스크 씨는 더 이상 값비싼 다른 산업 관행을 피할 수 없을 수도 있습니다. 하나는 마케팅입니다. 광고에 막대한 금액을 지출하는 다른 모든 대형 자동차 제조업체와 달리 Tesla는 제품을 홍보하기 위해 입소문과 Musk의 실제보다 더 큰 페르소나에 의존해 왔습니다. Barclays는 광고를 피하고 딜러를 거치지 않고 구매자에게 직접 판매함으로써 현재 판매하는 자동차 한 대당 $2,500-4,000를 절약할 수 있다고 생각합니다. 새로운 고객을 찾고 머스크가 440억 달러 규모의 사이드 프로젝트인 트위터의 양극화 관리로 테슬라 판매에 영향을 미칠 위험이 있기 때문에 회사는 이러한 절감액 중 일부를 포기할 가능성이 높습니다. 머스크는 처음으로 그의 회사가 "약간의 광고를 시도할 것"이라고 말하면서 그만큼 양보했습니다.테슬라가 뒤늦게 찾아온 또 하나의 자동차 제조 필수품은 가격 인하다. 머스크 씨는 할인을 제공하거나 재고가 쌓이는 것을 허용하지 않겠다고 약속했습니다. 그의 회사는 최근 두 가지를 모두 수행했습니다. 지난 5분기 동안 생산량이 판매량을 초과했습니다. 몇 년 동안 연평균 60%의 성장세를 보인 후 분기별 판매량은 2022년 2분기와 2023년 1분기 사이에 평균 30~40% 증가했습니다. 머스크는 더 많은 차량을 옮기기 위해 작년 말 가격을 인하하기 시작했으며 일부 모델에서는 최대 25%까지 가격을 인하했습니다. 2분기 매출은 1년 전에 비해 80% 이상 급증했습니다. 이면은 적법하게 수축하는 마진이었습니다. 투자자들은 경쟁사보다 머스크 씨의 가격 인하를 더 용인했습니다. 7월 17일 포드의 주가는 F-150 라이트닝 EV 픽업에 대한 막대한 할인을 발표한 후 6% 하락했습니다.다양한 비용이 증가함에 따라 Tesla는 다른 곳, 특히 제조 분야에서 비용을 계속 줄이려고 노력할 것입니다. 3월에는 생산 단계를 합리화하거나 심지어 제거하여 자동차를 "훨씬 더 간단하고 저렴하게" 만들도록 설계된 "unboxed process"를 공개했습니다. 머스크가 염두에 두고 있는 것이 정확히 무엇인지는 불분명하다. 그의 엔지니어링 독창성 기록에도 불구하고 모델 3용 로봇으로 사람을 대체함으로써 적어도 한 번의 이전 자동차 제조 시도는 머스크가 솔직하게 "생산 지옥"이라고 표현한 것과 2018년 거의 파산에 이르렀습니다.

'정책칼럼' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 암호화폐에 대한 이슬람권의 선호(23-7-14)/에코노미스트 (0) | 2023.07.21 |

|---|---|

| 중국이 배제된 배터리 공급망 불가능-환경정책과 안보정책의 충돌(23-7-17)/에코노미스트 (0) | 2023.07.21 |

| 세계는 제조업 망상에 사로잡혀 있다-수조 달러를 낭비하는 방법(23-7-13)/에코노미스트 (0) | 2023.07.21 |

| 기술사업화 재원의 제약과 기반 환경의 전환(23-7-14)/손수정.과학기술정책연구원 (0) | 2023.07.21 |

| The crypto ecosystem: key elements and risks(23-07-11)/.BIS (0) | 2023.07.19 |